Yuri Tsivian: Kino-Pravda No. 15–19 (1923–24)

The winter of 1922–23 was the high point of Vertov's experiments with titling. Another of Rodchenko's mobile constructions stars in Kino-Pravda No. 15 – this time reminiscent not of a globe, but of a hammer (the emblem of the Proletariat), which slowly rises to hit – what? Religion, of course. The inscription borne by this Constructivist "mobile" reads "With the hammer of knowledge." But (distinct from the previous issue of Kino-Pravda) the emphasis here is not on titles moving in real space, but on ones animated by photographic means. The credits specify: "Intertitles processed by the cameraman Boris Frantsisson. Moving intertitles: Ivan Beliakov and Mikhail Kaufman." A sham searchlight shines on a phrase, "On guard," from the pitch-dark night, and a giant "?" detaches itself from the background and slowly heads towards us. But the most astonishing process sequence in this film is the one featuring agitation artillery. Across a scene showing an artillery mortar in the middle of a wintry landscape preparing to fire (probably filmed during army manoeuvres), a large inscription appears, saying "Agit-shells." Fire! And a firework of newspapers is shown dispersing in the air. A political cliché given life by a film trick.

Tricks and politics – Vertov's two passions – make strange bedfellows. A review of Kino-Pravda No. 16 (also known as Spring Kino-Pravda), signed by "Z" (some zealot of funerals and parades), published by Pravda on May 25, 1923, accused Vertov of a lack of decorum: "Kino-Pravda, having filmed the May Day parade and the funeral of Vorovskii, considers that it has done its duty, and fecklessly captures on expensive film stock models demonstrating fashions in Petrovka street, or some acrobatic exercises by Proletkult students, to which there is absolutely no need to give broad popularity. The ... defect of the issues of Kino-Pravda is a motivation that is insufficiently serious (an attraction to tricks at all costs)."

But – we could object by the wisdom of hindsight – there is no telling what history will choose to remember. No doubt in May 1923 the recent killing of Vatslav Vorovskii (the Soviet delegate to the Lausanne Conference) by Maurice Conradi (a Russian émigré of Swiss descent, victimized earlier by the Soviet regime) made any other event look trifling, but had Vertov not included what his critic dismissed as "acrobatic exercises by Proletkult students" in the 16th issue of Kino-Pravda Sergei Eisenstein's first film, Dnevnik Glumova (Glumov's Diary), would have been lost.

Glumov's Diary was not a movie in the proper sense; it was never meant to be shown in movie theatres, just projected during a stage production. Eisenstein – then a Proletkult theatre director – wanted an on-stage movie show to be part of his eccentric production Mudrets (Wise Man), but as yet had neither the experience nor resources to film on his own. In 1923 the legendary feud between Eisenstein and Vertov (for more about which, see my book Lines of Resistance: Dziga Vertov and the Twenties) had not started. Eisenstein and Vertov (both associates of Left Front of the Arts) hit it off quite well, so Eisenstein asked Vertov, who agreed, to help with stock, camera, and cinematographer. It was to justify these expenses that Vertov included this footage in Kino-Pravda No. 16, under the heading The Spring Smiles of Proletkult. Of course, to a regular filmgoer not familiar with Eisenstein's theatre production, Glumov's Diary made little sense. No wonder Vertov's Spring Smiles made serious people like "Z" angry.

Kino-Pravda No. 17 credits Elizaveta Svilova as editor, and her work deserves it. Not one reviewer praised Vertov's Kino-Pravda for its "American montage" – here Svilova out-Americans the Americans. The sequence in which peasant women are shown binding sheaves contains shots less than a second long – some are as short as one-third of a second. Vertov and Svilova were especially fond of applying fast editing to work processes, as if by so doing they were helping people to work faster. Note also the pleasure Mikhail Kaufman's camera takes in making house-building scaffoldings look a little like giant Constructivist installations.

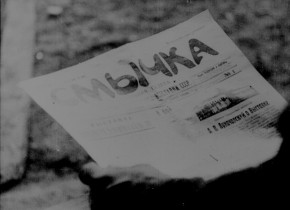

The centerpiece of this issue is the All-Union Agricultural Exhibition, with the alliance of workers and peasants as its central theme. Throughout the 1920s the word "alliance" (smychka – a specially coined one-word slogan) was used to refer to the partnership between two classes: the peasants and the workers, in whose name "the dictatorship of the proletariat" was declared. This term implied that the peasant majority was not oppressed under the proletarian hegemony, but was its lesser (non-hegemonic) partner. The All-Union Agricultural Exhibition in Moscow was part of the smychka campaign: the happy countryside's visit to the welcoming city. Kino-Pravda No. 17 is edited accordingly, cross-cutting shots of the countryside and shots taken in the city, and ending with workers and peasants reading the newspaper Smychka.

Just like Vertov's 1926 film A Sixth Part of the World, Kino-Pravda No. 18 and No. 19 (both 1924) belong to a peculiar – uniquely Vertovian – genre. Vertov called it probegi kinoapparata – movie-camera runs, or races, across far-apart geographic locations. The thrill of this genre is that these are all impossible travels, visionary voyages, imagined pan-planetary pans. Kino-Pravda No. 18 takes the viewer from West to East, Kino-Pravda No. 19, North to South; and A Sixth Part of the World is a movie journey around the vast territory of the Soviet Union.

The first of the three, Kino-Pravda No. 18 ("A race in the direction of Soviet reality"), was conceived as a journey on more than one level. It looks like a journey because Vertov starts with found footage filmed in Paris, and moves on to the footage shot in Russia, and it certainly feels like one – for the sequence that links Paris and Moscow has been assembled from travelling shots.

It is not just a camera race, it is a relay race: Vertov edits together various kinds of camera movement, reflecting the camera's mode of transport. We are first taken up the Eiffel Tower, its magnificent girders slowly gliding by (this movie-camera ascent, the title tells us, is dedicated to the memory of the tower's builder – Gustave Eiffel died in 1923). From there, a plane takes over. A title, "The movie camera lands in the territory of the USSR," is followed by a shot taken from the undercarriage of a descending airplane, as fields and meadows loom up rapidly below us. As the movie camera lands, it is taken over by a racing car ("Auto race Petrograd – Moscow," the title reads).

This is perhaps the closest Vertov's film practice ever came to his somewhat elusive theoretical concept of "intervals," formulated in his manifesto "We" in 1922:

"Kinoculism is the art of organizing the necessary movements of objects in space as a rhythmical artistic whole, in harmony with the properties of the material and the internal rhythm of each object. Intervals (the transition from one movement to another) are the material, the element of the art of movement, and by no means the movements themselves. It is they (the intervals) which draw the movement to a kinetic resolution."

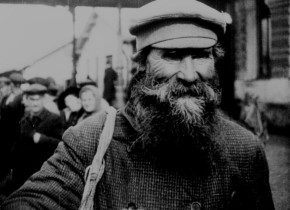

As usual, smychka (announced by its signature emblem, the handshake) is one of the dominant themes in Kino-Pravda No. 18, but here Vertov decides to illustrate it in an off-beat way. The movie camera picks out a bearded man in the crowd, who turns out to be a peasant, Vasilii Siriakov, who has come all the way from Yaroslav Province to see Moscow, and the camera shows us Moscow through the peasant's eye. "The movie camera pursues him," a title announces, whereupon a shadow of a man cranking a movie camera is shown. "The same peasant on his way to the Agricultural Exhibition" – and Siriakov is shown riding on a tram, all the while observing the tram conductor and the driver at work. The camera shadows our peasant everywhere. At one point he winds up in a Goskino workshop – at the moment when a baby is being Octobrized. What does this mean, "Octobrized"? The same as baptized – but in a workers' collective instead of a church, and into Communism rather than a religion. (Invented with an eye to replacing church christening, this stopgap ritual never took root.) What is the best name for a newborn boy? You guessed it – and in an extreme close-up, we see the name "Vladimir" emerging from a worker's mouth. All present are singing (guess which song?) as the boy is passed around – from a Communist worker to a Komsomol youngster and to a Young Pioneer. "To the Red Citizen Vladimir" (more singing faces) "grow healthy, Comrade" (close-up of hands holding the baby in the air). Workers at work. "Vladimir." Machine-tools at work. "Vladimir." The editing accelerates. "Vladimir." And intercut with all this, the recurrent shadow of the man with the camera, at work.

Kino-Pravda No. 19 tries to do many things at once – maybe a little too many for one reel. First, it contrasts cold and hot, winter and summer, Russia's arctic regions and Russia's Southern sea (named Black). Perhaps Eisenstein had a point when he said, with his usual deadly wit, that Vertov's dream was to lick Nanook and Moana in one fell swoop (see the chapter "Vertov versus Eisenstein" in Lines of Resistance). Secondly, Vertov dedicates this issue of Kino-Pravda to "Woman, peasant woman, worker woman," a theme which defines the dominant gender of this film, particularly towards the end. A young woman types; another woman milks a cow; another works a field, etc. Women in politics: a State woman speaks; Lenin's wife and sister – shown at Lenin's funeral, and by his side when he was still alive. And at the very end, pro domo sua: "The editing of the negative for Kino-Pravda No. 19," says the title, and Vertov's wife, the kinoc editor Elizaveta Svilova, is shown editing the very film we are watching. Déjà vu? If so, then in reverse: there is a similar sequence in Man with a Movie Camera, a film yet to be made.

There is also another sequence in Kino-Pravda No. 19 which anticipates a similar trick from Man with a Movie Camera (and, in a strange way, brings to mind that early British film, How It Feels to Be Run Over). This issue, as the one released before it, is a camera race, so images of women doing different jobs are connected by a recurrent subject: a train in movement, often with the movie camera mounted on the car roof. At one point a curious intertitle informs us: "4 metres of movie-camera memory, as it falls under the wheels of the freight train." The huge wheels flash by; a view from under the train. That's it. The last 4 metres of what the movie camera remembers. Evidently, in the eyes of the kinocs their kino-eye was a living being.

From: Yuri Tsivian, Catalogue "Le Giornate del Cinema Muto," Sacile/Pordenone 2004